Imagining plays a key role in thinking about possibilities. Modal terms like “could,” “should,” and “might” prompt us to imagine possible scenarios. I argue that imagination is the first step in modal cognition, as it generates the possibilities for consideration. The possibilities in the consideration set can then be partitioned into a more limited set of relevant possibilities, and ordered on some criteria, like value or probability.[1] Yet even imagination is not free, boundless, and unlimited. There are systematic constraints on imaginings. The three considerations that determine which possibilities are considered — physical possibility, probability or regularity, and morality — also influence which scenarios are imaginable or easier to imagine.

Ultimately, the evidence indicates that imagination uses a representation similar to the psychological representation of modality,[2] and operates under the constraints that apply to modal cognition in general. This paper has two key goals: (1) to strengthen the theory of a common underlying psychological representation of modality by applying it to imagination, and (2) to understand the imagination and its constraints better by illuminating the psychological representation it has in common with modal cognition.

1. Imagination as the Initial Generative Step of Modal Cognition

Modal cognition will be used as an umbrella term for any kind of thinking about possibility, including counterfactual thinking, causal selection, free will judgements, and more. Imagination is a sub-concept under modal cognition, as it is a form of “attention to possibilities.”[3] There are many types of imagination, but we can afford to gloss over most of the distinctions and instead use a broad definition. Imagination is to “represent without aiming at things as they actually, presently, and subjectively are.”[4] In other words, imagination is mental simulation. Since imagination is about non-occurrent possibilities – like fictional scenarios, images of the future, or counterfactuals – it is necessarily modal. But is modal cognition necessarily imaginative? In short: yes.

After all, we cannot represent possibilities based on a single proposition. Merely varying some proposition’s meaning or truth-value is a simple logical process that cannot characterize modal cognition in general, especially the rich kind of modal cognition involved in decision-making, causal judgements, and counterfactual reasoning. In modal cognition, we must conceive of a full scenario and then consider alternatives (possible worlds) for that scenario. This sounds a lot like imagination, which involves representing a situation: “a configuration of objects, properties, and relations.”[5] Considering the ways a captain could have prevented a ship from sinking, for instance, requires mentally simulating this scenario and varying its features to produce alternative possibilities.[6] Modal cognition relies on imagination to represent situations and generate their alternatives.

More precisely, imagination fits into modal cognition as the initial generative step: it produces the possibilities that are later considered and evaluated. This is inspired by the distinction between discriminative models and generative models in machine learning.[7] A discriminative model uses observed variables to identify unobserved target variables – for example, to find the probable causes of sensory inputs. These models often use a hierarchy of mappings between variables to represent an overall input-output mapping. In contrast, a generative model simulates the interactions among unobserved variables that might generate the observed variables. For example, graphics rendering programs can follow a set of processes to simulate a physical environment. Williams (2020) provides detailed evidence showing that both perception and imagination are best described as generative models.

While I will not repeat William’s arguments here, treating imagination as a generative model is valuable for a few additional reasons. First, imagination is governed by principles of generation: a set of (implicit or explicit) rules that guide our imaginings.[8] For example, in Harry Potter, “Latin words and wands create magic” is a principle of generation that readers can consistently use to simulate the imagined world. Rather than a graphics rendering program that deterministically yields a given outcome by following certain processes, the imagination generates a set of possibilities guided by the relevant principles of generation. However, imagination, like rendering, is a generative model that uses certain processes to produce (and explain) a set of phenomena.

Second, treating imagination as a generative model explains imaginative mirroring: unless prompted otherwise by principles of generation, our imagination defaults to follow the rules of the real world. If a cup ‘spills’ in an imaginary tea party, the participants will treat the spilled cup as empty, following the physics of reality.[9] In perception, we are always running a generative model of reality, using processes we derive from experience to simulate the physical world and predict its behavior.[10] Imagination involves running a generative model on top of this simulation of reality. Some processes are modified in the imagining, but the ones that are not modified are ‘filled in’ by our default generative model of reality. Further, we quarantine imaginative models from perceptual models, so that events in the imagining are not taken to have effects in the real world – imagined spills do not make the real table wet. Treating imagination as a generative model running separately but based upon a reality-based perceptual model is useful in explaining these effects.

Finally, the generative model view explains the systematic constraints on imagination and their function. Imaginings are not utterly free and boundless. Rather, imagination changes some aspects of the world, and then unfolds the impacts of these changes in a constrained way based on specific rules of generation. Later, I will show that imagination by default follows our world’s laws of physics and probability. We also resist imaginings that break normative limitations set by morality. If imagination is a generative model, then the constraints are the rules that determine how the generation process is carried out, analogous to rendering algorithms in animations or games. Imagination’s constraints allow it to serve a valuable and adaptive function in generating possibilities relevant to our real world.

In Kratzer semantics, a modal anchor is the element from which a set of possible worlds is projected.[11] In simpler terms, the anchor is the thing held constant in modal projection. For example, in the statement “people could jump off this roof,” the modal anchor is the situation of the roof. We project a domain of possible worlds that all include this roof and determine if people jump off the roof in at least one possible world. Imagination is the cognitive function that carries out modal projection, as it generates the possibilities prescribed by the modal anchor and its context. The modal anchor defines the processes of the generative model. Alternatively, modal anchors correspond to “props” in the philosophy of imagination, where a prop is the thing that prescribes what is to be imagined and the principles of generation to be used in imagining.[12] The modal anchor functions as a linguistic prop, prescribing an imagining that generates a set of possibilities relevant to the anchor.

![]() This sets the stage for a comprehensive picture of modal cognition. First, some prop or modal anchor elicits thought about possibilities and triggers the start of the process. Second, imagination acts as a generative model, creating a set of possibilities based on the rules of generation prescribed by the modal anchor. This produces the consideration set, the group of possibilities under consideration. Third, the generated possibilities can then be narrowed down further and partitioned into a relevance set.[13] Finally, the possibilities are ordered according to some criteria, so the possibilities most relevant to the task at hand are ranked the most highly.

This sets the stage for a comprehensive picture of modal cognition. First, some prop or modal anchor elicits thought about possibilities and triggers the start of the process. Second, imagination acts as a generative model, creating a set of possibilities based on the rules of generation prescribed by the modal anchor. This produces the consideration set, the group of possibilities under consideration. Third, the generated possibilities can then be narrowed down further and partitioned into a relevance set.[13] Finally, the possibilities are ordered according to some criteria, so the possibilities most relevant to the task at hand are ranked the most highly.

While it is conceptually helpful to separate these steps, I do not claim the steps occur in a sequential, discrete order. These components can happen synchronously and are often blurred together. Steps two and three are especially entangled, as I will show that generation through imagination also involves constraints that winnow down the considered possibilities. The rest of this paper will examine step two in detail. I will focus on how the imagination is constrained, and how its constraints indicate that it involves the psychological representation of modality.

2. The Psychological Representation of Modality and Imagination

2.1 Constraints in Modality

A growing body of research shows that a common psychological representation underlies many kinds of thinking about possibilities. Using certain constraints, this representation supports quick, effortless, computationally cheap, and often unconscious modal cognition. The constraints of physics, morality, and probability influence which possibilities are considered relevant.[14] For instance, in counterfactual reasoning, we mostly consider probable events, evaluatively good events, and physically normal events. Evidence also indicates that a common psychological capacity underlies our judgements of moral permissibility and physical possibility.[15] Evaluative concerns and prescriptive norms play an especially critical role in constraining possibilities.

Phillips, Luguri, and Knobe (2015) show that morality plays a key role in limiting the set of relevant possibilities for many types of judgement. For instance, people are less likely to agree that a captain on a sinking ship was forced to throw his wife overboard than that he was forced to throw cargo overboard. With the added support of several other studies, researchers demonstrated this effect occurs because immoral possibilities are considered less relevant. Critically for my thesis, the researchers also showed that prompting participants to generate more possibilities led to significant effects on their judgements.[16] When participants imagined decisions the captain could have made, they were more likely to judgements that he was free and not forced. This demonstrates the importance of the initial generative step.

Further, Phillips and Cushman (2017) found that both children and adults under time constraints tend to judge immoral events as impossible.[17] Non-reflective modal judgements are “ought-like,” and exclude immoral possibilities from consideration. Given time to deliberate, adults can differentiate types of modal judgment and make more reasoned judgements about possibility. In this study, participants were presented with events and were asked to judge which events were possible. For example, for the person stuck at an airport, participants are asked if he can hail a taxi, teleport, sell his car, or sneak onto public transit. Importantly, the generative step is performed by the researchers. The participants do not have to imaginatively generate the options. Instead, they are given the options and asked to evaluate their possibility. This skips step 2 of modal cognition, and instead focuses on step 3. However, in most natural situations, we have to generate the available options ourselves.

In general, research on modal cognition overlooks the mechanism that generates possibilities. Existing studies often ask participants to evaluate already-generated possibilities. This experimental design systematically misses the effects of the process that generates possibilities in the first place. One exception is Kushnir and Flanagan (2019), which tested whether a person’s ability to generate possibilities predicted their judgement that they have free will.[18] We tend to judge agents as free when we can represent alternative possibilities for their action. Thus, simply generating more possibilities may lead us to judge that agents are freer. Indeed, this experiment found that children’s fluency in generating ideas predicted their evaluation of their own free will. Performance on a task that involved generating ideas within an imagined world was the best predictor of a child’s judgements: the more fluent the children were in this imagination task, the more likely they were to judge themselves as free.

The researchers speculated that there may be a “direct pathway from idea generation to judgments of choice and possibility.”[19] In my view, the pathway is indirect, as existing research indicates that after possibility-generation we also evaluate the relevance of possibilities and rank them. However, the studies discussed above underscore the importance of the imagination as the initial generative step. The nature and quantity of the generated possibilities has demonstrable impacts on modal judgements. Furthermore, there may be important constraints on this generation process that lead to downstream effects on later processes in modal cognition.

2.2 Constraints in Imagination

The same constraints apply to both modality and imagination. This is surprising, as intuitively imagination seems far freer and more limitless than normal reasoning. We can easily imagine worlds where magic violates physical laws or where improbable events occur often. However, I argue that the default representation of imagination results in resistance to imagining possibilities that violate physical laws, irregular or unlikely possibilities, and immoral or evaluatively bad possibilities. Experimental results reveal that the imaginations of young children are limited by precisely these constraints. Adults are able to deliberately generate more and less constrained possibilities. However, just as adults can treat immoral possibilities as irrelevant, imaginative resistance shows that the adult imagination is inhibited against immoral possibilities. Conclusively, the imagination shows a startling resemblance to the psychological representation of modality.

Investigations of modal cognition often use developmental research to show constraints on children’s reasoning about possibilities, indicating a default representation of modality that is especially visible during early childhood.[20] Similarly, the imaginations of young children (ages 2-8) are surprisingly reality-constrained. Children tend to resist, or fail to generate, impossible and improbable imaginings. When prompted to imagine hypothetical machines, children judge that familiar machines could be real, but are reluctant to imagine possible machines that operate very differently from any object they have regular experience with.[21] Children also protest against pretense that contradicts their knowledge of regularity, expecting imaginary entities to have ordinary properties.[22] Even when pretending, kids expect lions to roar and pigs to oink, and they resist imagining otherwise.

Furthermore, 82% of the time, children extend fantasy stories with realistic events rather than fantastic events, while adults extend fantasy stories with fantastic events.[23] Young children imagine along ordinary lines even when primed with fantastical contexts, filling in typical and probable causes for fantastical imaginary events.[24] Children show a strong typicality bias in completing fictional stories, favoring additions to the story that match their regular experiences in reality.[25] For example, even if an imagined character can teleport or ride dragons, a young child will say the character gets to the store by walking and arrives at school on a bus. Children’s bias toward adding regular events persisted even after experimental manipulations designed to encourage children to notice a pattern of atypicality in the story.[26] This is surprising: popular wisdom dictates that children are exceptionally and fantastically imaginative. However, this research shows that children have simple, limited, and relatively mundane imaginations that are constrained by regularity, probability, and typical reality.

Evaluative concerns are an additional constraint on the imagination. My theory predicts that children’s imaginations will show a bias toward generating evaluatively good possibilities, and a resistance to imagining possibilities that they see as evaluatively wrong. Some studies indicate that this is the case. For example, American children are more likely than Nepalese and Singaporean children to judge that they are free to act against cultural and moral norms.[27] This is likely because children in cultures with stronger or more restrictive evaluative norms find it harder to generate evaluatively wrong possibilities or see these possibilities as relevant. As free will judgements depend on representing alternative possibilities, these children see themselves as less free to pursue possibilities that violate evaluative norms. This means that morality is an additional constraint on the imagination, especially in early childhood. However, more research is needed to validate this hypothesis.

As children develop, the constraints on their imagination relax, leading to less restricted generation of possibilities. Older children are more likely to imagine improbable and physically impossible phenomena.[28] Explicitly prompting children to generate more possibilities leads them to imagine more like older children, producing possibilities less constrained by probability and regularity.[29] This shows that the initial generative step may underlie observed developmental changes in modal cognition. The imaginations of older children generate more total possibilities, including more irregular possibilities, and they are therefore more likely to judge irregular events as possible.

Viewing imagination as a generative model allows productive interpretations of this research. When imagining, young children apply a generative model with the same rules of generation used in perception to produce expectations about reality. This early imagination may use simple constraints and empirical heuristics to allow effortless and rapid generation of possibilities. For instance, if the child regularly encounters an event, they are more likely to imagine this event.[30] In later development and adulthood, the imagination generates possibilities in a more deliberative and analytical way. This suggests a dual process model of imagination.[31] Children may use a more uncontrolled, effortless, and unconscious imagination based on simple heuristics and experience-derived rules of generation. In contrast, adults use a more controlled, effortful and conscious imagination that generates possibilities based on relatively sophisticated and principled rules.

Although adults can more easily imagine irregular events or events that violate physical laws, the developed imagination is still constrained by moral norms. Imaginative resistance refers to a phenomenon where people find it difficult to engage in prompted imaginative activities. For example, if a fiction prompts us to imagine that axe-murdering is morally good, we resist this imagining. Unfortunately, there are few empirical tests of imaginative resistance. In one study conducted by Liao, Strohminger, and Sripada (2014), participants exhibited resistance to imagining morally deviant scenarios.[32] For example, participants reported difficulty in imagining that it was morally right for Hippolytos to trick Larisa in the Greek myth “The Rape of Persephone,” even though Zeus declared the trickery was morally right.[33] Their imaginative difficulty was significantly correlated with their evaluation that this trickery was morally wrong. This effect was replicated in a second experiment with a different story. The experiments also showed that imaginative resistance was modulated by context and genre. Participants more familiar with Greek myth were less likely to resist imagining that Hippolytos’ trickery was right, and participants were more willing to imagine that child sacrifice is permissible in an Aztec myth than in a police procedural. Context-specific variation in imaginative resistance may explain some of the variation in modal judgements.

Further research has demonstrated the empirical reality of imaginative resistance. In one study, adults were asked to imagine morally deviant worlds, where immoral actions are morally right within the imagined world.[34] Most participants found morally deviant worlds more difficult to imagine than worlds where unlikely events occurred often, but easier to imagine than worlds with conceptual contradictions. Participants classified these morally deviant worlds as improbable, not impossible, although a subset reported an absolute inability to imagine a morally deviant world. Another study employed a unique design to avoid the effects of authorial authority and variation in prompts, asking participants to create morally deviant worlds themselves and describe these imagined worlds in their own words.[35] Participants still exhibited resistance to imagining moral deviant worlds, even when they were the authors of the world. Disgust sensitivity was correlated with imaginative resistance, while need for cognition and creativity were correlated with ease of imagining. Finally, Black and Barnes (2017) constructed an imaginative resistance scale to support future research on this phenomenon and its correlations with individual differences.

Taken as a whole, the research discussed above provides strong support for the view that imagination and thinking about possibilities involve the same psychological representation. This default representation is most visible in early childhood, but it still operates in adulthood, especially under time-constraints or in scenarios involving immoral possibilities. Imaginative resistance shows that the primacy of morality in limiting the imagination corresponds to the primacy of morality in limiting which possibilities are considered relevant. Overall, this shows that generation of possibilities through imagination and evaluations of possibility relevance both involve a common psychological representation that is present at all stages of modal cognition.

2.3 Neuroscience of Imagination & Modal Cognition

This paper primarily aims to describe imagination and modal cognition on Marr’s computational and algorithmic levels of analysis, without delving into the neural implementation. However, any complete model of modal cognition will describe the neural implementational details. Furthermore, an implication of my view is that interactions between imagination and modal cognition will be visible on a neural level. One falsification of my view could show that these two processes do not interact or involve very distinct neural pathways. As such, the limited review of the neuroscientific evidence below is meant only to establish the plausibility of two key claims: (1) modal cognition involves imagination, and (2) imagination and modal cognition use similar neural mechanisms.

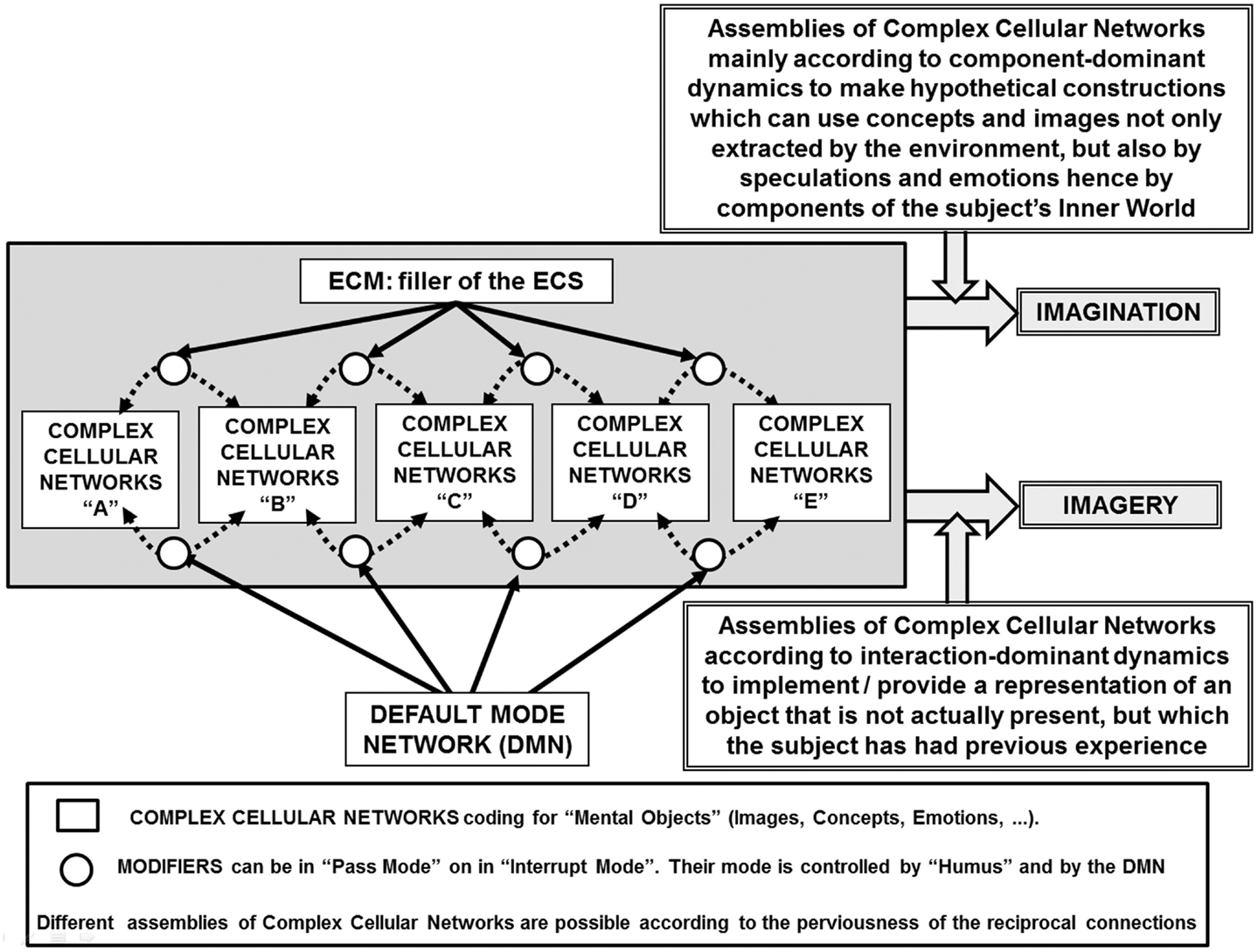

Neuroscientific evidence shows that modal cognition and imagination involve the same neural correlates. There is a growing consensus that remembering the past, imagining the future, and counterfactual thinking all involve similar neural mechanisms in the default mode network (DMN).[36] Several studies show that the DMN is involved in simulating possible experiences, imagining, and counterfactual thinking.[37] At the outset, this indicates that modal cognition and imagination use the same parts of the brain. But more specifically, future-oriented and counterfactual thinking engages the posterior DMN (pDMN), centered around the posterior cingulate cortex.[38] Researchers showed this by asking participants in an fMRI scan to make choices about their present situation, and then prospective choices about their future. Their findings demonstrated that people often engage vivid mental imagery in future-oriented thinking, and that this process activates the pDMN while reducing its connectivity with the anterior DMN. This provides a candidate neural process that underlies imaginative generation of possibilities.

One prominent neuroscientific theory of the imagination. See "The Neurobiology of Imagination: Possible Role of Interaction-Dominant Dynamics and Default Mode Network."

Furthermore, a key cognitive ability that underlies imagination is prefrontal synthesis (PFS), the ability to create novel mental images. This process is performed in the lateral prefrontal cortex (LPFC), which likely acts as an executive controller that synchronizes a network of neuronal ensembles that represent familiar objects, synthesizing these objects into a new imaginary experience.[39] Children acquire PFS around 3 to 4 years of age, along with other imaginative abilities like mental rotation, storytelling, and advanced pretend play.[40] Similarly, young children tend to lack a distinction between immoral, impossible, and irregular counterfactuals – they often conflate “could” and “should.”[41] While further study is needed, it is plausible that development of PFS is associated with mature modal cognition, making modal distinctions, and generating more sophisticated imaginings.

3. Conclusion

This essay constructs a broad theory of modal cognition in which imagination plays a critical role. Namely, imagination serves as an initial step that generates the possibilities for consideration for later steps. Imagination is best described algorithmically as a generative model which operates based on rules of generation prescribed by a modal anchor. Furthermore, the evidence discussed in section 2 indicates that imagination and thinking about possibilities both use a default psychological representation with the same fundamental constraints. While this psychological representation is not always visible in adulthood, it is clear in early childhood, and it still has observable effects in adult cognition. The psychological representation of modality and imagination enables us to think about possibilities in rapid, effortless, and useful ways.

This theory also yields testable predictions that could be explored by future empirical research. For example, it predicts that young children will exhibit more imaginative resistance to violations of morality than adults. They will be more likely to classify morally deviant worlds as impossible or show a total inability to imagine these worlds.[42] Under time pressure, adults will exhibit more imaginative resistance, and they will be more likely to imagine valuable scenarios than dis-valuable scenarios – just as people are more likely to generate valuable possibilities under time pressure.[43] Correspondingly, people given more time and opportunity to engage the imagination might exhibit more willingness to imagine morally deviant worlds. With very limited time or significant cognitive pressure, adult imaginations may resemble the imaginations of young children. Finally, individual differences in openness to experience, creativity, and imaginative ability may predict some of the variation in possibility judgements, through differences in the generation of possibilities. For instance, people who naturally generate more possibilities will be more likely to judge agents as free rather than forced.

Existing research has not explicitly drawn this connection between the imagination and the psychological representation of modality. Even if this proposed model is not correct as a whole, I hope this paper can help integrate disconnected research projects on modal cognition and imagination in cognitive science, neuroscience, and philosophy.

Bibliography

Addis, Donna Rose, Alana T. Wong, and Daniel L. Schacter. “Remembering the past and imagining the future: common and distinct neural substrates during event construction and elaboration.” Neuropsychologia 45, no. 7 (2007): 1363-1377.

Barnes, Jennifer, and Jessica Black. “Impossible or improbable: The difficulty of imagining morally deviant worlds.” Imagination, Cognition and Personality 36, no. 1 (2016): 27-40.

Black, Jessica E., and Jennifer L. Barnes. “Measuring the unimaginable: Imaginative resistance to fiction and related constructs.” Personality and Individual Differences 111 (2017): 71-79.

Black, Jessica E., and Jennifer L. Barnes. “Morality and the imagination: Real-world moral beliefs interfere with imagining fictional content.” Philosophical Psychology 33, no. 7 (2020): 1018-1044.

Berto, Francesco. “Taming the runabout imagination ticket.” Synthese (2018): 1-15.

Bowman-Smith, Celina K., Andrew Shtulman, and Ori Friedman. “Distant lands make for distant possibilities: Children view improbable events as more possible in far-away locations.” Developmental psychology 55, no. 4 (2019): 722.

Cook, Claire, and David M. Sobel. “Children’s beliefs about the fantasy/reality status of hypothesized machines.” Developmental Science 14, no. 1 (2011): 1-8.

Cushman, Fiery. “Action, outcome, and value: A dual-system framework for morality.” Personality and social psychology review 17, no. 3 (2013): 273-292.

Gaesser, Brendan. “Constructing memory, imagination, and empathy: a cognitive neuroscience perspective.” Frontiers in psychology 3 (2013): 576.

Goulding, Brandon W., and Ori Friedman. “Children’s beliefs about possibility differ across dreams, stories, and reality.” Child development (2020).

Kind, Amy. “Imagining under constraints.” Knowledge through imagination (2016): 145-59.

Kratzer, Angelika, “Modality for the 21st century,” In 19th International Congress of Linguists, pp. 181-201. 2013.

Lane, Jonathan D., Samuel Ronfard, Stéphane P. Francioli, and Paul L. Harris. “Children’s imagination and belief: Prone to flights of fancy or grounded in reality?” Cognition 152 (2016): 127-140.

Leslie, Alan M. “Pretending and believing: Issues in the theory of ToMM.” Cognition 50, no. 1-3 (1994): 211-238.

Liao, Shen-yi and Tamar Gendler. “Imagination.” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2020 Edition). Edward N. Zalta (ed.). <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2020/entries/imagination/>.

Liao, Shen-yi, Nina Strohminger, and Chandra Sekhar Sripada. “Empirically investigating imaginative resistance.” British Journal of Aesthetics 54, no. 3 (2014): 339-355.

Moulton, Samuel T., and Stephen M. Kosslyn. “Imagining predictions: mental imagery as mental emulation.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 364, no. 1521 (2009): 1273-1280.

Parikh, Natasha, Luka Ruzic, Gregory W. Stewart, R. Nathan Spreng, and Felipe De Brigard. “What if? Neural activity underlying semantic and episodic counterfactual thinking.” NeuroImage 178 (2018): 332-345

Pearson, Joel. “The human imagination: the cognitive neuroscience of visual mental imagery.” Nature Reviews Neuroscience 20, no. 10 (2019): 624-634.

Phillips, Jonathan, Adam Morris, and Fiery Cushman. “How we know what not to think.” Trends in cognitive sciences 23, no. 12 (2019): 1026-1040.

Phillips, Jonathan, and Fiery Cushman. “Morality constrains the default representation of what is possible.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114, no. 18 (2017): 4649-4654.

Phillips, Jonathan, and Joshua Knobe. “The psychological representation of modality.” Mind & Language 33, no. 1 (2018): 65-94.

Phillips, Jonathan, Jamie B. Luguri, and Joshua Knobe. “Unifying morality’s influence on non-moral judgments: The relevance of alternative possibilities.” Cognition 145 (2015): 30-42.

Schubert, Torben, Renée Eloo, Jana Scharfen, and Nexhmedin Morina. “How imagining personal future scenarios influences affect: Systematic review and meta-analysis.” Clinical Psychology Review 75 (2020): 101811.

Shtulman, Andrew, and Jonathan Phillips. “Differentiating “could” from “should”: Developmental changes in modal cognition.” Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 165 (2018): 161-182.

Shtulman, Andrew, and Lester Tong. “Cognitive parallels between moral judgment and modal judgment.” Psychonomic bulletin & review 20, no. 6 (2013): 1327-1335.

Spreng, R. Nathan, Raymond A. Mar, and Alice SN Kim. “The common neural basis of autobiographical memory, prospection, navigation, theory of mind, and the default mode: a quantitative meta-analysis.” Journal of cognitive neuroscience 21, no. 3 (2009): 489-510.

Stuart, Michael T. “Towards a dual process epistemology of imagination.” Synthese (2019): 1-22.

Thorburn, Rachel, Celina K. Bowman-Smith, and Ori Friedman. “Likely stories: Young children favor typical over atypical story events.” Cognitive Development 56 (2020): 100950.

Van de Vondervoort, Julia W., and Ori Friedman. “Preschoolers can infer general rules governing fantastical events in fiction.” Developmental psychology 50, no. 5 (2014): 1594.

Van de Vondervoort, Julia W., and Ori Friedman. “Young children protest and correct pretense that contradicts their general knowledge.” Cognitive Development 43 (2017): 182-189.

Vyshedskiy, Andrey. “Neuroscience of imagination and implications for human evolution.” (2019). Preprint DOI: 10.31234/osf.io/skxwc.

Weisberg, Deena Skolnick, and David M. Sobel. “Young children discriminate improbable from impossible events in fiction.” Cognitive Development 27, no. 1 (2012): 90-98.

Weisberg, Deena Skolnick, David M. Sobel, Joshua Goodstein, and Paul Bloom. “Young children are reality-prone when thinking about stories.” Journal of Cognition and Culture 13, no. 3-4 (2013): 383-407.

Williams, Daniel. “Imaginative Constraints and Generative Models.” Australasian Journal of Philosophy (2020): 1-15.

Williamson, Timothy. “Knowing by imagining.” Knowledge through imagination (2016): 113-23.

Winlove, Crawford IP, Fraser Milton, Jake Ranson, Jon Fulford, Matthew MacKisack, Fiona Macpherson, and Adam Zeman. “The neural correlates of visual imagery: A co-ordinate-based meta-analysis.” Cortex 105 (2018): 4-25.

Xu, Xiaoxiao, Hong Yuan, and Xu Lei. “Activation and connectivity within the default mode network contribute independently to future-oriented thought.” Scientific reports 6 (2016): 21001.

Phillips, Jonathan, Adam Morris, and Fiery Cushman, “How we know what not to think,” Trends in cognitive sciences 23, no. 12 (2019): 1026-1040. ↑

Phillips, Jonathan, and Joshua Knobe, “The psychological representation of modality,” Mind & Language 33, no. 1 (2018): 65-94. ↑

Williamson, Timothy, “Knowing by imagining,” Knowledge through imagination (2016): 113-23. Pg. 4. ↑

Liao, Shen-yi and Tamar Gendler, “Imagination,” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. ↑

Berto, Francesco. “Taming the runabout imagination ticket.” Synthese (2018): 1-15. ↑

Phillips, Luguri, and Knobe. “Unifying morality’s influence on non-moral judgments: The relevance of alternative possibilities,” Cognition 145 (2015): 30-42. ↑

The difference between discriminative and generative models is (roughly) similar to the distinction between model-free and model-based reinforcement learning – see Cushman (2017). ↑

Walton, Kendall L, Mimesis as make-believe: On the foundations of the representational arts, Harvard University Press, 1990. Pg. 53. ↑

Leslie, Alan M, “Pretending and believing: Issues in the theory of ToMM,” Cognition 50, no. 1-3 (1994): 211-238. ↑

Williams, “Imaginative Constraints and Generative Models,” 2020. ↑

Kratzer, Angelika, “Modality for the 21st century,” In 19th International Congress of Linguists, pp. 181-201. 2013. ↑

Walton, Mimesis as Make-believe, pg. 47. ↑

Phillips, Morris, and Cushman, “How we know what not to think,” (2019). ↑

Phillips and Knobe (2018). ↑

Shtulman, Andrew, and Lester Tong, “Cognitive parallels between moral judgment and modal judgment,” Psychonomic bulletin & review 20, no. 6 (2013): 1327-1335. ↑

This was shown in the second “manipulation” studies for each type of judgement (1b, 2b, 3b, and 4b). ↑

Phillips and Cushman (2017). ↑

Flanagan, Teresa, and Tamar Kushnir, “Individual differences in fluency with idea generation predict children’s beliefs in their own free will,” Cognitive Science, pp. 1738-1744. 2019. ↑

Flanagan and Kushnir, pg. 5. ↑

For instance, see Shtulman, Andrew, and Jonathan Phillips, “Differentiating “could” from “should”: Developmental changes in modal cognition,” Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 165 (2018): 161-182. ↑

Cook and Sobel, “Children’s beliefs about the fantasy/reality status of hypothesized machines,” Developmental Science 14, no. 1 (2011): 1-8. ↑

Van de Vondervoort, Julia W., and Ori Friedman,” Young children protest and correct pretense that contradicts their general knowledge,” Cognitive Development 43 (2017): 182-189. ↑

Weisberg et al, “Young children are reality-prone when thinking about stories,” Journal of Cognition and Culture 13, no. 3-4 (2013): 383-407. Pg. 386. ↑

Lane et al, “Children’s imagination and belief: Prone to flights of fancy or grounded in reality?,” Cognition 152 (2016): 127-140. Pg. 131. ↑

Thorburn, Bowman-Smith, and Friedman, “Likely stories: Young children favor typical over atypical story events,” Cognitive Development 56 (2020): 100950. ↑

Thorburn, Bowman-Smith, and Friedman (2020). ↑

See Chernyak, Kang, and Kushnir (2019) and Chernyak et al (2013). ↑

Lane et al, pg. 6. ↑

See Lane et al, pg. 8; Goulding and Friedman, “Children’s beliefs about possibility differ across dreams, stories, and reality,” Child development (2020); and Bowman-Smith et al, “Distant lands make for distant possibilities: Children view improbable events as more possible in far-away locations,” Developmental psychology 55, no. 4 (2019): 722. ↑

Goulding and Friedman (2020). ↑

Stuart, Michael T, “Towards a dual process epistemology of imagination,” Synthese (2019): 1-22. ↑

Liao, Shen-yi, Nina Strohminger, and Chandra Sekhar Sripada, “Empirically investigating imaginative resistance,” British Journal of Aesthetics 54, no. 3 (2014): 339-355. ↑

Liao, Strohminger, and Sripada (2014), pg. 10. ↑

Barnes and Black (2016), “Impossible or improbable: The difficulty of imagining morally deviant worlds,” pg. 8. ↑

Black, Jessica E., and Jennifer L. Barnes, “Morality and the imagination: Real-world moral beliefs interfere with imagining fictional content,” Philosophical Psychology 33, no. 7 (2020): 1018-1044. ↑

Mullally, Sinéad L., and Eleanor A. Maguire, “Memory, imagination, and predicting the future: a common brain mechanism?” The Neuroscientist 20, no. 3 (2014): 220-234. ↑

Pearson (2019); Gaesser (2013); Addis et al (2007); Spreng et al (2009); and Winlove et al (2018). ↑

Xu, Xiaoxiao, Hong Yuan, and Xu Lei, “Activation and connectivity within the default mode network contribute independently to future-oriented thought,” Scientific reports 6 (2016): 21001. ↑

Vyshedskiy, Andrey. “Neuroscience of imagination and implications for human evolution.” (2019). Preprint DOI: 10.31234/osf.io/skxwc. ↑

Vyshedskiy, “Neuroscience of Imagination.” ↑

Shtulman, Andrew, and Jonathan Phillips. “Differentiating “could” from “should”: Developmental changes in modal cognition.” Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 165 (2018): 161-182. ↑

See Barnes and Black (2016). ↑

Phillips, Jonathan, and Fiery Cushman, “Morality constrains the default representation of what is possible,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114, no. 18 (2017): 4649-4654. ↑